In a move that has largely flown under the radar outside China, the country’s Supreme Court issued a landmark judicial interpretation on 1 August. The ruling legally voided any contractual agreement—regardless of a mutual “voluntary waiver” (in exchange for higher take-home pay)—that exempts an employer from paying social insurance contributions. These informal arrangements, particularly common among blue-collar workers and short-term hires, have been the norm for years. Now, the courts have made it clear: there is no such thing as opting out of social insurance.

A laudable goal with a potentially heavy near-term burden

While English-language media coverage has been minimal, domestic media has applauded the move as a concrete victory for workers’ welfare. But beneath the celebratory headlines lies a more complex reality: enforcing full social insurance contributions may increase labor costs by as much as 30% for small- and medium-enterprise (SME) employers. Employees themselves, already under wage pressure, are also likely to see lower disposable incomes due to their own required contributions.

SMEs face an immediate financial squeeze, while workers take home less pay in the short term. The long-term policy goal is laudable—expand social coverage, reduce China’s high precautionary savings rate and boost domestic consumption. But the near-term burden could be heavy, especially for China’s ever-resilient yet increasingly beleaguered private sector.

Finding ways to fill up the fiscal coffer

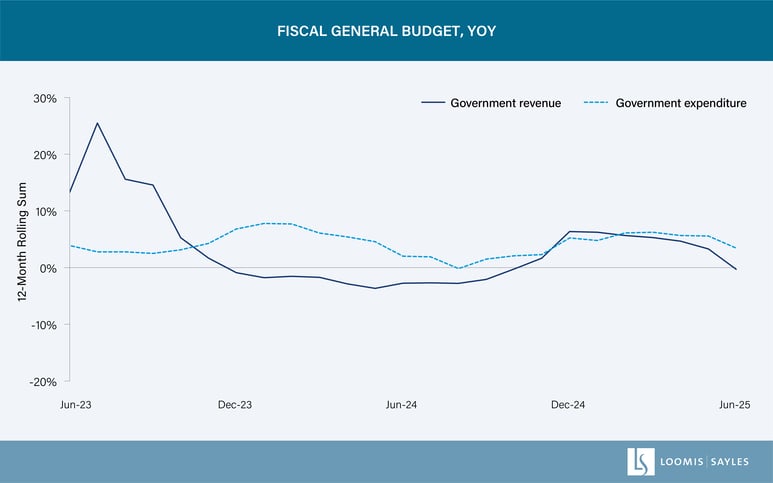

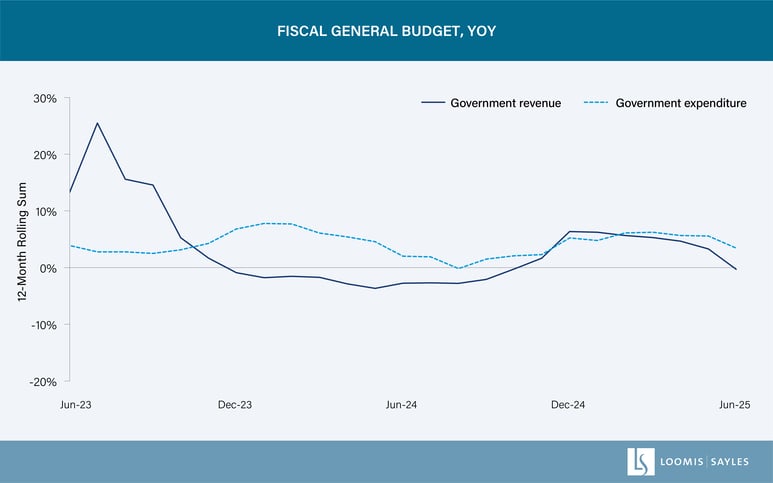

Why did this ruling happen now? I suspect fiscal imperatives are driving this shift. The timing is noteworthy. In a parallel move to bolster state revenue, China announced the reinstatement of a value-added tax (VAT) on interest income from government and financial bonds, ending a decades-long exemption. The third arrow in China’s fiscal push is tighter enforcement of taxes on overseas income, leveraging the Common Reporting Standard (CRS). Since joining the CRS in 2017, China has gained access to financial data from more than 100 jurisdictions, enabling comprehensive cross-checks of declared income. Numerous mainland Chinese have reported receiving text messages and phone calls from tax authorities about their overseas investments, which I see as a clear sign that Beijing is actively using this powerful tool. This heightened scrutiny is no longer limited to the ultra-wealthy but is increasingly targeting the middle class as well.

Source: CEIC, as of June 2025. The chart presented above is shown for illustrative purposes only. Some or all of the information on this chart may be dated, and, therefore, should not be the basis to purchase or sell any securities. The information is not intended to represent any actual portfolio. Information obtained from outside sources is believed to be correct, but Loomis Sayles cannot guarantee its accuracy. This material cannot be copied, reproduced or redistributed without authorization.

Watching for the impact on the private sector

This flurry of new measures, in my view, signals Beijing’s intent: broaden the state’s revenue base, tighten compliance and shift more of the social welfare financing burden onto employers—and by extension, the private sector. The coming years will show how far these policies go and who ultimately bears the cost. Viewed together, I believe investors may be underestimating the macroeconomic impacts of these developments. SMEs in the private sector could face serious challenges from rising labor costs, while private consumption may be undermined by slower growth in disposable income.

8274709.1.1