Congress has moved fast on a fiscal stimulus package. This surprised me in some ways. In my last blog post, I talked about how the 50/50 Senate split might push policy toward the center. That may still happen with other parts of President Biden’s agenda, but Democrats appear to be steering fiscal policy to the left.

The House and the Senate have passed identical budget resolutions that authorize deficit spending for President Biden’s full $1.9 trillion fiscal stimulus proposal. I had expected a smaller bipartisan deal. With this approach, it looks like the Democrats will attempt to use their narrow majority to pass President Biden’s proposal on a party-line basis. This approach is not without risks.

Racing against the clock

Congressional leaders are aiming to pass the final legislation by March 13, when extended unemployment benefits expire, to avoid a lapse in the benefits. (These benefits were renewed through March 13 in the fiscal package passed at the end of last December.)

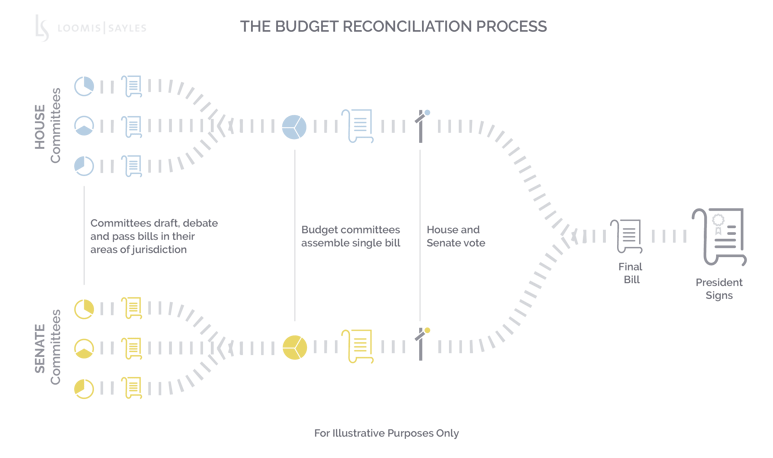

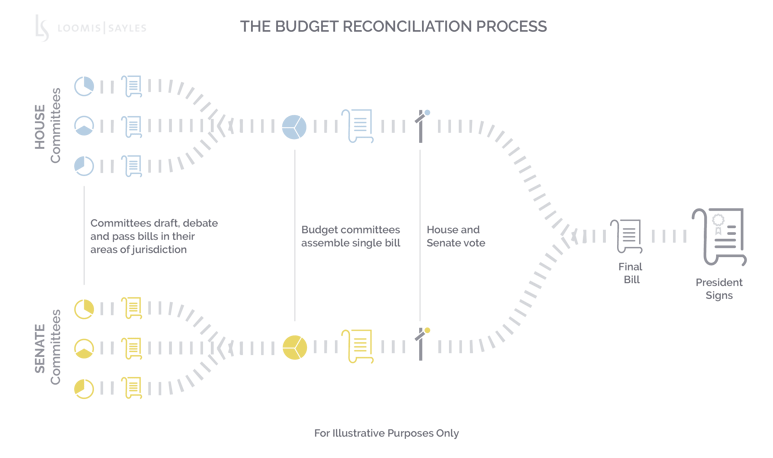

The budget resolution process includes many different committees and steps. It’s possible for a final package to pass by March 13, but it might take until late March if things do not go smoothly.

What could go wrong?

A budget passed with a budget resolution must come to a vote. There can be no filibuster, so it needs only a simple majority to pass. With a 50/50 tie in the Senate, Democrats can’t afford any defectors because there likely won’t be any Republican support.

If congressional Democrats in the House and Senate unanimously support a single pre-negotiated package, Congress should be able to get the bill to the President in early March. But political disagreements, even within Democrat ranks, could delay enactment until perhaps mid-to-late March.

Pondering the long-term impact

I think Congress will ultimately pass the fiscal package in late March. It may be somewhat smaller than the proposed $1.9 trillion, and I doubt it will include Biden’s proposed minimum wage hike. This package could be close to twice as large as the fiscal package passed in December. Some recent macroeconomic data have been upbeat and the pace of vaccinations seems to be picking up. I think the US economy is likely in for strong growth in 2021 and 2022.

The longer-term implications of the fiscal stimulus appear less clear, and that’s something I am still pondering. A federal budget deficit of around $3.4 trillion in fiscal year 2021 is plausible, following a deficit in FY 2020 of $3.1 trillion. A movement called “Modern Monetary Theory” seems to have gained influence among some Democrat policymakers. Some in Congress seem to like the idea that the US could create money to jumpstart the economy and achieve full employment with little concern for inflation. That may work in the short run, but in the longer run, the Fed would likely need to raise interest rates to contain inflation, and then we would discover just how expensive a large national debt can be.

I am more cautious about this type of approach, especially in light of some current difficulties. First, people may save most of any money they receive. In economic terms, saving means not buying goods and services; paying bills (for example, one’s mortgage or credit card balances) is considered saving, not spending. If people choose to save their relief payments, what portion of these payments will make its way into the economy?

Second, what will people buy? If the pandemic continues to hobble the service sector, people aren’t likely to spend much on services. Next, where will the goods come from? If goods purchased from big retailers come directly or indirectly from outside the US, much of the stimulus could end up stimulating other economies.

If the “marginal propensity to consume” is low enough, or the “marginal propensity to import” is high enough, the fiscal multiplier may be low, meaning the government won’t get much bang for its buck.

In my view, what would ultimately help fix the economy is a comprehensive vaccination program this year, which would accelerate an end to pandemic restrictions and allow the suffering service sector to return to more normal operations. Won’t it be lovely to go to a concert, a game or a restaurant again, just like we did a year ago? To me, the economy is like a coiled spring being pushed down by the pandemic. When the pandemic has receded, the spring should rebound. Fiscal support can play a role in the recovery by helping consumers pay their bills until employment returns to normal and by helping small businesses stay afloat until their customers return.

MALR026847