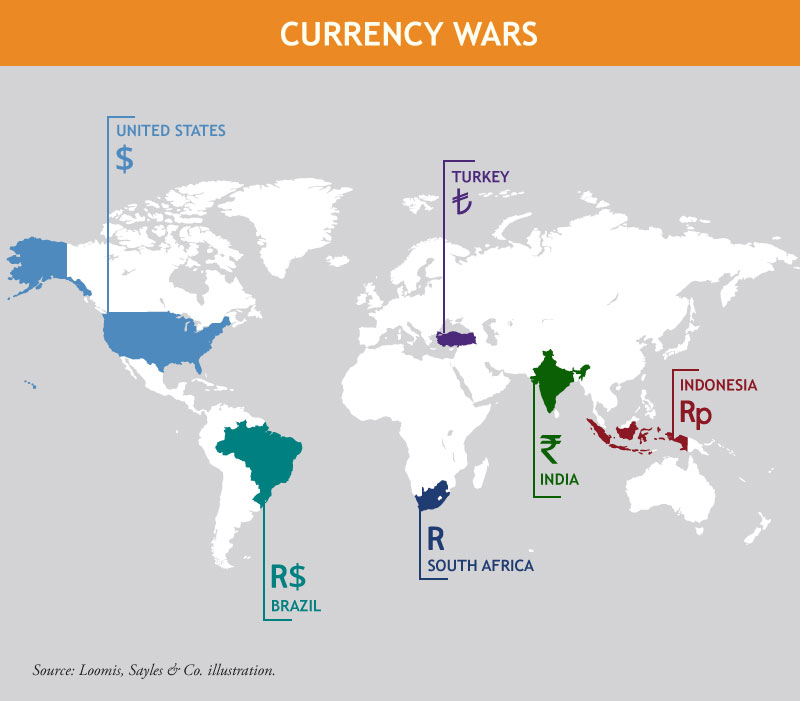

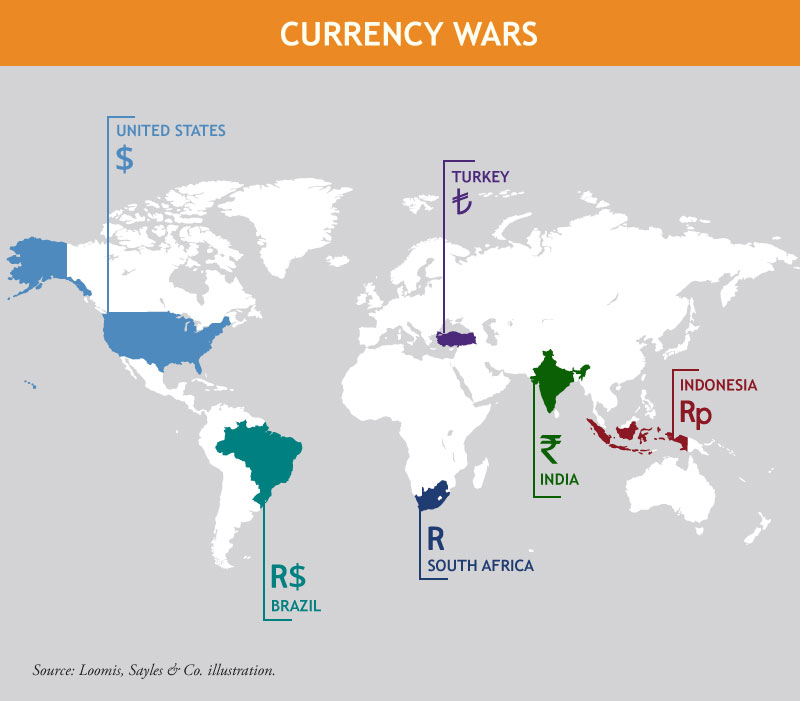

The term “currency war" may sound like sensationalism. But the series of competitive devaluations in global currency markets over the past several years have essentially created a series of global currency battles.

The Fed Fired First

It was the US who fired the first shot back in 2008 when the Fed introduced quantitative easing (QE) during the midst of the global financial crisis. They followed by reinforcing the troops via QE2 in 2010, which resulted in an outcry of protest from the central banks of emerging markets who feared a wave of capital flows upon their economies – a dangerous side effect of QE2 that had the potential to destabilize these economies over the long term by encouraging misallocations of capital, excessive credit growth, asset price inflation, and inflated currency values.

As I look at the global economic landscape five years later, it appears that the fears of those EM central bankers may have been well-founded. Years of capital inflows to emerging economies are now rapidly reversing, often leaving a tidal wave of volatility in their wake. The result has been sharply depreciating exchange rates for the weakest of EM economies, coupled with rising US dollar borrowing costs. The currency depreciation has, in many cases, led to imported inflation pressures, which, in combination with weak growth due to diminished credit flows, created stagflationary economic conditions.

What’s a banker to do?

This has placed many EM central bankers in an extraordinarily difficult bind. They cannot ease monetary policy to stimulate growth as they normally would in such a situation – easing policy would likely only make matters worse for them with respect to capital outflows. Nor can they afford to risk stoking inflationary pressures further. This unfavorable fundamental backdrop currently characterizing the economies of Brazil, Turkey and South Africa, tends to create a negative feedback loop, which begins with weak growth, rising capital outflows, lower currency values, higher imported inflation, tighter monetary policy, and eventually weaker growth still, in response to all of these developments; none of which are good for asset values, only complicating matters further.

What could break the cycle?

The good news is that many EM currencies have become quite undervalued compared with long-term measures of fair value. This could help support their export competitiveness, despite declines in the currencies of other large export-oriented economies including Germany, Japan, and China, where currency depreciation has been less severe. The other key variable is stronger global growth. Most emerging markets economies are dependent to some degree on external demand. Furthermore, better global growth can lift animal spirits among investors and make them more willing and comfortable to invest in beleaguered EM economies that are badly in need of their capital.

I see pockets of value in emerging markets assets today; but for now they are generally still badly in need of a fundamental catalyst to help unlock the opportunity.

MALR014248