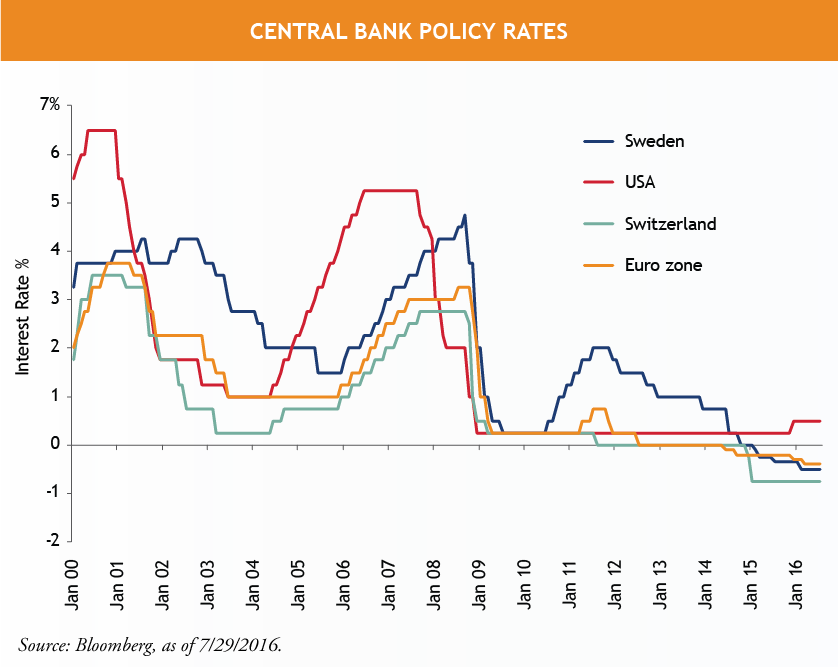

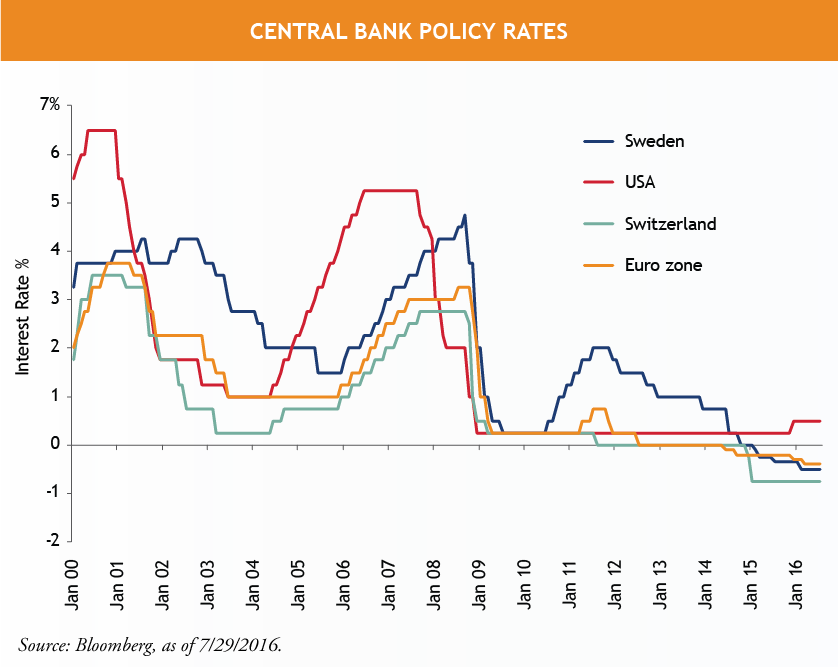

Historically, central banks raise interest rates on bank deposits when they want to cool inflation and cut interest rates when they want to stimulate the economy. Since banks pass these changes on to their customers, higher interest rates can make borrowing more expensive and saving money more attractive. Until recently, an interest rate of zero seemed to be the lowest central banks could go and negative interest rates were unthinkable.

Interest rates mechanics upended

But that has all changed. Negative interest rates have become useful for central banks, because it gives them a way to stimulate the economy when rates are already low. Japan, the Eurozone, Switzerland and Sweden all currently have central bank rates below zero, meaning banks now have to pay that country’s central bank for their deposits. And it’s not just short-term interest rates that are negative. Five-year bond yields in Japan, Germany, France, the Netherlands and Switzerland are also below zero. Japan and Switzerland have both issued long-term government bonds at negative interest rates, meaning that an investor who buys and holds a bond until maturity is guaranteed to lose money. (And it may not be out of the question for well-known global companies to issue bonds at negative interest rates someday soon.)

Negative interest rates: bad news for banks

Negative interest rates push down the lending rates that banks charge their customers – and it’s extremely difficult for banks to offset that lost revenue by charging customers for deposits. Banks in some countries with negative interest rates have started charging interest on deposits to large companies and very wealthy individuals. So far, none have dared to do the same to all individual depositors, many of whom are living off a pension. Banks are unpopular enough even without appearing to snatch money from the elderly.

Could we pay interest on a deposit account and receive interest on a mortgage?

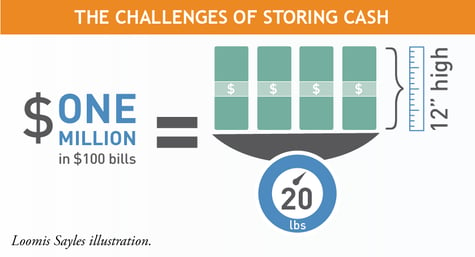

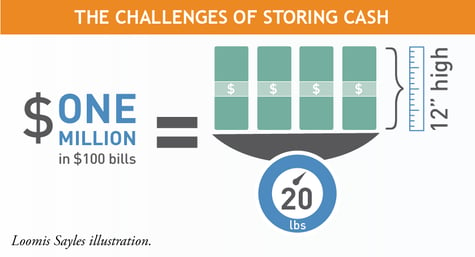

Not likely. Banks are under political pressure not to impose negative interest rates on ordinary savers. The euro zone and Switzerland have both negative interest rates and high denomination bank notes, which makes it easier to store cash. However, those high denomination notes are becoming harder to obtain. In May, the European Central Bank (ECB) announced that it will no longer print 500 Euro notes. This note was nicknamed ‘the Bin Laden’ for its popularity among terrorists, drug dealers and money launderers, who were presumably disappointed by the ECB announcement. But ending production of the 500 euro note will also make it harder (or at least more uncomfortable) for law-abiding citizens to store cash under the mattress.

Not likely. Banks are under political pressure not to impose negative interest rates on ordinary savers. The euro zone and Switzerland have both negative interest rates and high denomination bank notes, which makes it easier to store cash. However, those high denomination notes are becoming harder to obtain. In May, the European Central Bank (ECB) announced that it will no longer print 500 Euro notes. This note was nicknamed ‘the Bin Laden’ for its popularity among terrorists, drug dealers and money launderers, who were presumably disappointed by the ECB announcement. But ending production of the 500 euro note will also make it harder (or at least more uncomfortable) for law-abiding citizens to store cash under the mattress.

Holding cash at home is one way to avoid negative interest rates on deposit accounts but it’s not foolproof -- you might get robbed or lose it in a fire. Keeping it in a bank safe deposit box is safer, but some banks no longer offer that option.

Could cash be abolished?

Some believe physical cash might one day be abolished altogether. This isn’t as fanciful as it sounds. Bank of England chief economist Andy Haldane has discussed abolishing physical cash and shifting to an electronic wallet as a way to stop people from hoarding cash if interest rates go well below zero. In the near term, it is more likely that central banks will follow the lead of Europe and the UK and shift away from printing the highest denomination bank notes.

Could negative interest rates be introduced in the United States?

I think it is possible. Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen described it as a last resort, but didn’t rule it out. The largest banks had to test their readiness for it as part of the 2016 Federal Reserve stress tests. It might happen if there’s a recession before the Fed has raised interest rates sufficiently for a cut to still-positive levels to stimulate a recovery.

MALR015590

Not likely. Banks are under political pressure not to impose negative interest rates on ordinary savers. The euro zone and Switzerland have both negative interest rates and high denomination bank notes, which makes it easier to store cash. However, those high denomination notes are becoming harder to obtain. In May, the European Central Bank (ECB) announced that it will no longer print 500 Euro notes. This note was nicknamed ‘the Bin Laden’ for its popularity among terrorists, drug dealers and money launderers, who were presumably disappointed by the ECB announcement. But ending production of the 500 euro note will also make it harder (or at least more uncomfortable) for law-abiding citizens to store cash under the mattress.

Not likely. Banks are under political pressure not to impose negative interest rates on ordinary savers. The euro zone and Switzerland have both negative interest rates and high denomination bank notes, which makes it easier to store cash. However, those high denomination notes are becoming harder to obtain. In May, the European Central Bank (ECB) announced that it will no longer print 500 Euro notes. This note was nicknamed ‘the Bin Laden’ for its popularity among terrorists, drug dealers and money launderers, who were presumably disappointed by the ECB announcement. But ending production of the 500 euro note will also make it harder (or at least more uncomfortable) for law-abiding citizens to store cash under the mattress.