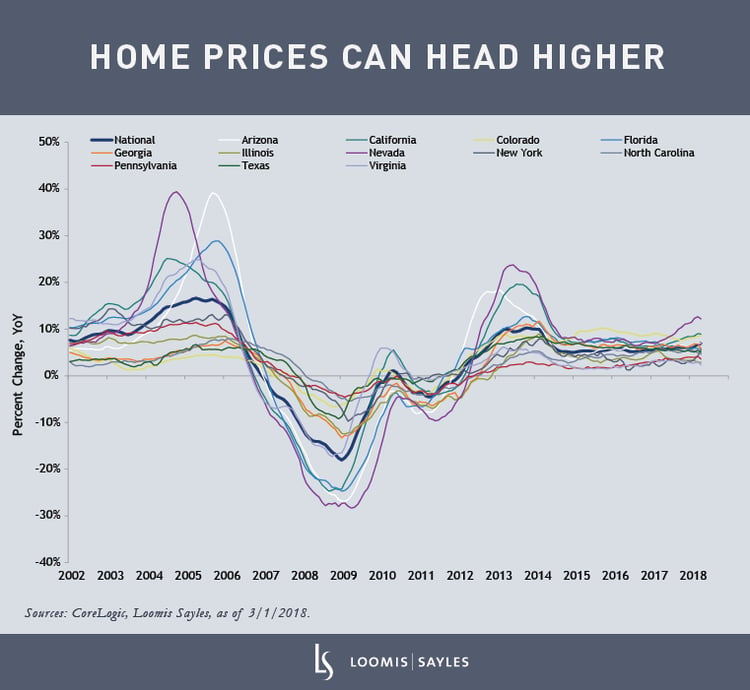

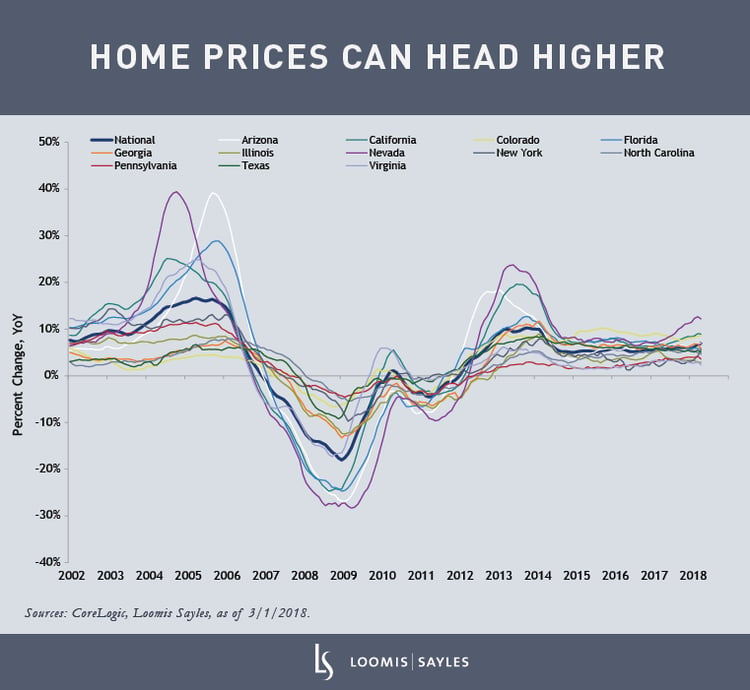

There’s a tug of war brewing between housing costs and consumer budgets in the US. Single-family home prices have risen 6% a year or more since 2011[1], and supply/demand forces point to further increases. But consumer budgets have limits. Some buyers are now spending around half of their income on housing.

Over time, rising home prices and interest rates should put pressure on either home price appreciation, consumer consumption or both. But near term, I think home prices can still go higher.

Here’s a look at the factors driving home prices and how higher housing costs are affecting consumers.

Housing shortage, higher prices in single-family homes

The US is short 7.3 million single-family homes according to some estimates,[2] a major factor boosting prices.

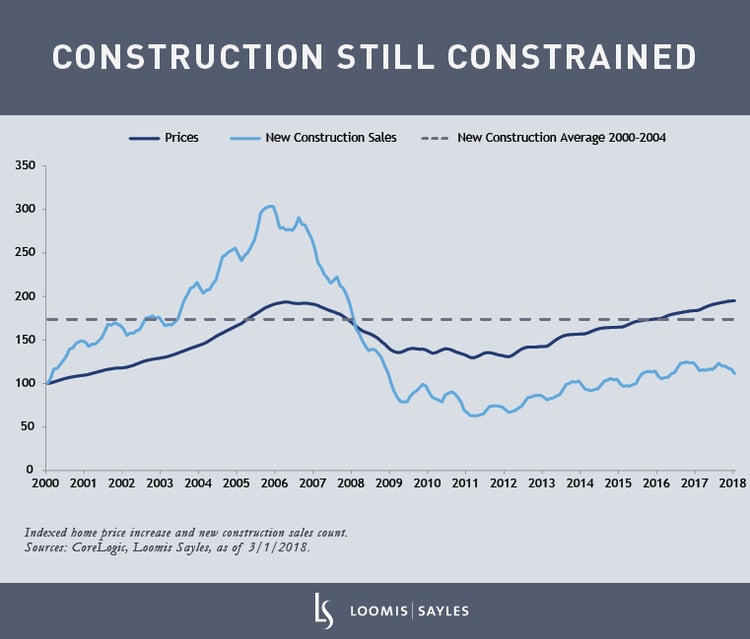

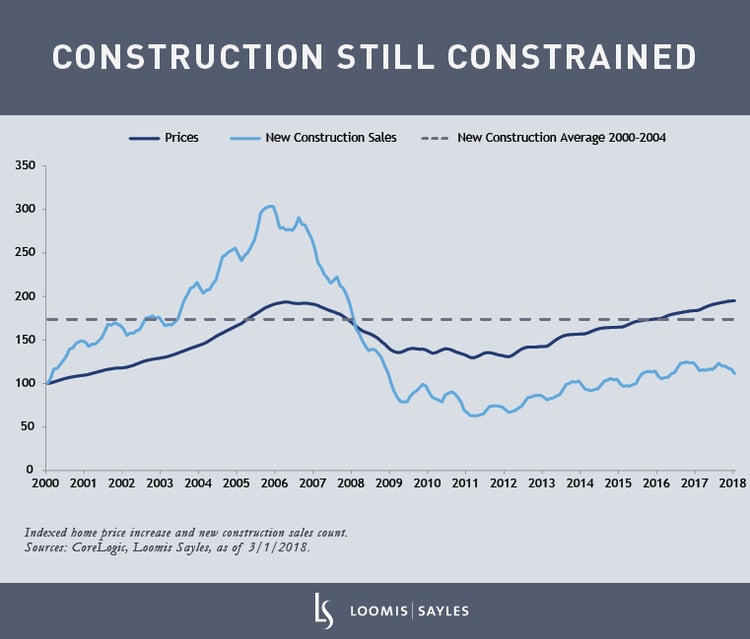

New construction remains far below pre-crisis levels, held back by land, labor and funding constraints. Demand for single-family homes is highest in a handful of densely populated cities, which have very little land to develop. Environmental and zoning regulations continue to tighten, making it more difficult to develop the land that is available.

The nation’s pool of construction workers has shrunk since the housing bust, when years of inactivity drove many workers to abandon the construction industry. And construction is financed mostly through local banks, which cut back their construction lending after suffering large losses during the crisis. As a result, loans are harder to get, and interest rates are much higher.

Meanwhile, population growth continues, exacerbating the shortage.

Higher labor and materials costs are also a factor. New construction supplies the market with additional homes when there is a shortage, so home prices are likely to grow at least at the rate of new construction inflation. Costs for construction materials rose significantly in 2017-2018.

Housing costs are a heavy burden for many consumers

Home buyers still need a place to live in this tight supply market, but many are at uncomfortable debt-to-income levels. House prices are increasing faster than incomes. And thanks to rising mortgage rates, borrower payment burdens are growing even faster than prices. With the recent rise in rates, roughly 10%-20% of GSE borrowers[3] have debt-to-income levels of 40% or more[4], which is considered very stretched. When taxes are factored into the calculation, these consumers are spending more than 50%[5] of their post-tax income just to pay for housing (mortgage, taxes, insurance), which is likely unsustainable.

For would-be buyers who find themselves priced out of the market, renting is no longer a cheaper alternative. Today, renting is just as expensive as owning. Unlike the 2000-2008 period, when house prices went up much faster than rents, rental rates since 2008 have risen faster than home prices.

Home prices win out for now

Over the next few years, I think home prices will win the tug of war against consumer budgets. I believe low supply, rising household formation, foreign demand, and loosening credit can support 4% to 5% annual price increases over the next two to three years, above the long-term trend of CPI plus 1 percentage point.

While affordability is beginning to be stretched, mortgage underwriting remains very tight. As a result, even consumers with high debt-to-income ratios are well-tested in their ability and willingness to carry the extra debt. Housing-related investment sectors, such as mortgage credit, should stay supported in this environment.

But the housing market, and its role in the economy, is approaching an interesting inflection point. For the past seven years, the recovery in home prices was a sign of recovery in the overall economy. We are entering a period when what is positive for US housing is not necessarily positive for the US economy: lack of single-family construction lowers economic growth and puts extra pressure on the consumer budgets. I will be watching this development closely.

[1] CoreLogic Combined National Home Price, December 2011 to December 2017

[2] Housing Underproduction in the US; April 2018, Up for Growth National Coalition

[3] GSE stands for government-sponsored enterprises, which include Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and Federal Home Loan Banks; GSE borrowers refers to borrowers whose loans will be acquired by GSEs.

[4] Source: Loomis Sayles analysis of recent Credit-Risk Transfer (CRT) deals

[5] Source: Loomis Sayles analysis of recent Credit-Risk Transfer (CRT) deals

MALR022049