It is highly likely that the European Central Bank (ECB) will introduce additional easing measures at its first meeting of the year this Thursday, Jan 22nd. Under the most flexible policy option, the bank would commit to purchases of some set size per month, perhaps €50 billion, across a range of private and public assets. We believe there is a:

- High probability purchases will include sovereign bonds

- Strong probability of including corporate bonds

- Reasonable probability of including other assets, including supranational bonds

- Some chance of including equities, a highly potent policy choice, and one that is not currently on the market’s radar at all

Sovereign purchases without risk sharing?

Some members of the Governing Council, including but not only Germany, are already uncomfortable with the current set of purchases (covered bonds and asset-backed securities). We also know they are highly allergic to the idea of government bond purchases. They have tended to be more comfortable with central bank intervention during times of market failure dysfunction, but we are not dealing with that type of situation.

Some members of the Governing Council, including but not only Germany, are already uncomfortable with the current set of purchases (covered bonds and asset-backed securities). We also know they are highly allergic to the idea of government bond purchases. They have tended to be more comfortable with central bank intervention during times of market failure dysfunction, but we are not dealing with that type of situation.

One structure, reported to have been agreed between the ECB and the German government, involves individual countries bearing the risk of their own sovereigns, rather than risk sharing across the eurosystem (ECB plus the euro zone national central banks). For example, if the ECB bought €10 billion of Italian bonds, the Bank of Italy would be responsible for some or all losses that could occur on those bonds.

We believe this structure will undercut the perceived impact and effectiveness of the program from the outset. Markets want a clear demonstration that the euro area is committed to “one for all and all for one.”

To date, the market has largely ignored the ECB’s demonstrated reluctance toward such risk sharing. In 2011, when the ECB expanded its collateral framework to include additional credit claims (ACC), they broke this risk-sharing solidarity. Under the ACC framework, the national central banks can accept previously ineligible collateral, but they must bear the risks.

This gets to the fundamental, unresolved, intractable problem underlying the euro crisis that there is STILL have no solution for. The jury is still out on whether euro area countries are willing to backstop each other.

Will euro area leaders choose solidarity, integration, and more federalism, or choose national sovereignty?

We believe if the ECB goes ahead with sovereign purchases subject to caveats, automatic shut-offs or size limitations, it will undermine market confidence in the program’s effectiveness from the start. Markets are currently uncertain that buying sovereign bonds will produce the desired outcome of improved economic growth. Of note:

- Policymakers would likely buy according to the ECB capital key, so purchases would be 26% weighted toward Germany and just 2% weighted toward Portugal or Ireland. We’ve weighted these percentages to include the participation of non-euro area National Central Banks (NCBs).

- The ECB Governing Council has shown great sensitivity to the idea of rewarding moral hazard—that is, by buying bonds of “profligate” sovereigns, you undercut governments’ willingness to reform.

- Finally, the euro area financial system has been far more reliant on bank intermediation than the US, so the impact of central bank purchases is different. Europe has more keenly needed healthy banks providing credit to the real economy in order to drive economic growth.

It’s far from clear that ECB purchases of government bonds would meaningfully improve the credit outlook for the real economy.

We still see room for the ECB to start more private sector asset purchases in coming months.

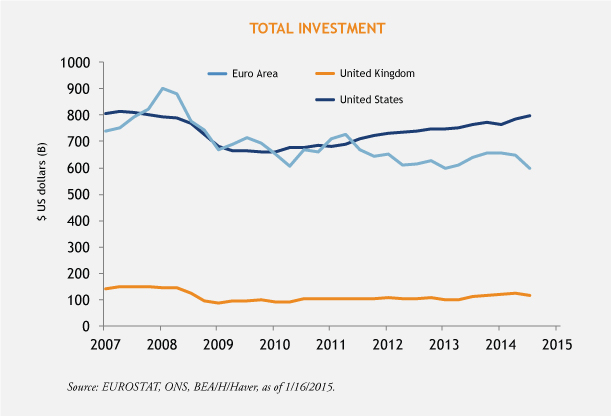

In our view, the most powerful and durable policy options for improving European growth and sustainability must involve increasing investment and reinforcing equity. In the years preceding the crisis, many European corporate sectors were overly reliant on debt financing instead of equity. Since then, total economy investment has floundered and in some countries, even those without housing busts, has cratered compared to the rebounds seen in the US and UK.

Although monetary policy alone seems unable to spur investment, the ECB could use its balance sheet to buy equities. EU leaders could build a pooled fund to provide capital to small-and medium-sized businesses. They could coordinate fiscal policy to incentivize fresh private investment via depreciation and tax rules.

The new Juncker Investment Plan, created by the EU Commission, is in the right spirit, but has just a kernel of public funds. It hinges upon ¾ of funding coming from the private sector, and seems unlikely to achieve its goal of €300 billion (around 3% of GDP) in investment over 3 years. Certainly, there’s more room for creative capital solutions by the ECB, looking to build its balance sheet, and governments looking to raise their countries’ long-run growth rates.

*Source: European Central Bank, capital subscription. The capital of the ECB comes from the national central banks (NCBs) of all EU Member States.

MALR012810

Market conditions are extremely fluid and change frequently.

This blog post is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as investment advice. Any opinions or forecasts contained herein reflect the

subjective judgments and assumptions of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect the views of Loomis, Sayles & Company, L.P. Information, including

that obtained from outside sources, is believed to be correct, but Loomis Sayles cannot guarantee its accuracy. This material cannot be copied, reproduced or

redistributed without authorization. This information is subject to change at any time without notice.